San Cristobal and the Braided Revolucionistas

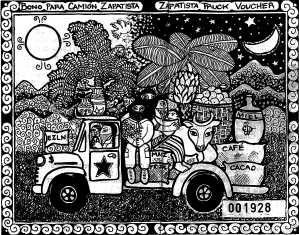

Reading: « How Subcomandante Marcos Employed Strategic Communication to Promote the Zapatista Revolution »

San Cristobal de Las Casas is a somber town painted in dusty Mexican-style colors– beautiful, but showing its slip. The city is located in Chiapas, a problematic province with a history of revolution and contest. Its legacy has been supporting and advocating for its own people and land, against social and economic injustices unsolved or instituted by the Mexican Government. Western tourists, pulled in capitalist and anti-capitalist directions, never knew what to think. Every movie theater in town showed nightly documentaries on Castro’s Cuba and Zapatista’s Liberacion Nacional. Every wall stenciled with quirky and artistic anti-corporate graffiti. Although they were inspired by Che Guavara and other socialist heroes, Subcomandante Marcos (el lider revolucionario) insists that “[the Zapatistas didn’t go to war to kill or be killed” but rather “went to war in order to be heard.” These are local issues being solved by local leaders. He was a brilliant strategic communicator. Dissent Magazine remarks that the Zapatistas spearheaded “negotiation about what it means to be Indian within a larger Mexican nation… and [created] a communication and public debate deeply rooted in popular cultural idioms.” By creating militias to generate publicity and enlist sympathizers, the goals of the revolucionarios are and have been education, health care, and political voice—equal rights, equal opportunities for a forgotten population.

This autonomous spirit is the palpable spark in San Cristobal, combining crisp mountain air and ancient cultural roots demanding preservation. It questions what it means to understand rules, or laws—namely Western rules and laws.

Not having spent long in Mexico, and being deeply shielded by the paved paths of the Yucatan Peninsula, I was shocked to wake up on my overnight bus to see children carrying large buckets of fresh water to their thatched huts. The cliffs underneath our bus, rocks dropping quietly to the long bottom, did not seem so scary to these children as it did to us. Our surroundings were transformed from tropical sandy coast to mountains of lush rain forest, but cold and stony. We entered a shielded community, nestled in remote hills. This place felt forgotten. There were political protests the day we arrived. In Chiapas and Latin America, these are as common as rain in the jungle. Caballeros held signs demanding “Justicia para Chiapas” and “Derechos Iguales” for Maya. More than 100 men sat peacefully outside of the Catedral de San Cristobal de Las Casas for three days (the entire time we were there), under tarps during the rain, and under sombreros in the sun. The centro mercado, a vast and wild array of local food and craft, demanded full attention as the full skinned heads of las vacas stared blankly at us as we walked by. Toasted crickets with chile waited patiently in their deep baskets. Heather ate a pound of them, I nearly gagged on my first.

Navigating the local buses, San Cristobal has the narrowest streets I have ever experienced—room for about one pedestrian, with sharp turns and 1.5 foot high curbs. It is a city built for walking and navigation, but the standards, are mercilessly different. After loading into a crowded small local van, we traveled about half an hour outside of San Cristobal to Chumas, which harbors la Iglesia de San Juan Bautista, a church which looks like white wedding cake with blue and green icing on its edges. Two small boys operate the entry door and gently say, “gracias senorita para tu visita, y por favor, no sacar fotografias.” Not that you have a chance of ever forgetting what is on the inside of the church but rather, wanting to photograph the inside of the church only to prove to the listeners of your story that you are not lying about la iglesia. Large and dark with no pews and fresh pine needles strewn across the floor, so that you do not see any floor, there are nearly fifteen altars that seem close to igniting the church in full flame, but never does. Each family who visited brought a chicken (which they would later sacrifice during prayer) came with nearly 50 tall, thin beeswax candles which they stood in 3 or 4 rows, waiting for the candles to become one large lake of hot wax. While candles and incense burn, a shaman, standing on one leg and chanting, lifts his folded hands to the air. A woman sways a sick young girl over the candles, singing and prostrating, while her husband and other children look on. Coca Cola is placed as offerings in front of 40 adorned statues of saints, heavily cloaked and cared for, safely guarded behind glass, while visitors slowly pass by. Outside of the church, the market slowly moves through the hours of the day, unconcerned about the happenings of the church, or the shocked faces of visitors.